How to Use a Compass to Find Your Way

These days, a whole lot of people rely on GPS devices to help them get from point A to point B with ease. While GPS devices sure are convenient, though, they don’t replace a good ol’ fashioned compass.

If SHTF and you need to navigate your way to shelter or safety, the ability to use a compass to find your way is critical. Without proper navigation skills, you could get lost and get yourself stuck in the wilderness for days, weeks, or even months.

So, to help you master the art of navigating with a compass, I’ve created this guide to all things compass-related. Up next, I’ll walk you through the basics of what a compass is and how it works. I’ll also teach you how to use a compass and a map to navigate in any situation.

Plus, I’ll even answer some of your most common questions about compasses so you can feel confident whenever you need to use a compass in real life. Let’s get to it.

Table of Contents

What Is A Compass?

A compass is a tool used for navigation that shows direction in relation to north. You can use a compass to shoot a bearing (i.e. to determine the direction of an object), or to navigate a course on land, water, or in the air without the use of fixed reference points.

Types of Compasses

If someone asked you to picture a compass in your mind, the vast majority of us would think of a small circular object with a spinning needle that points toward magnetic north.

While this is certainly one type of compass there are actually many different variations of compasses in the world today.

The two main types of compasses are magnetic compasses and gyrocompasses.

A magnetic compass has a built-in magnetic element (usually a needle or a card) that will point toward magnetic north by aligning with the Earth’s magnetic field.

A gyrocompass, however, is a type of non-magnetic compass. Gyrocompasses contain a fast-spinning disk that uses the rotation of the earth to automatically determine direction.

A gyrocompass has two main advantages over a magnetic compass:

- Point To True North. Unlike a magnetic compass, which points to the magnetic north pole, a gyrocompass points to true north (i.e. the direction of the geographic north pole). This means you don’t need to adjust for variation or declination when plotting a course or taking a bearing (more on that later).

- Not Affected By Metals. The accuracy of a magnetic compass is affected by nearby metals (called deviation). Since a gyrocompass isn’t magnetic, it won’t be affected by the metal on a ship or plane.

Even though gyrocompasses have some great advantages over a magnetic compass, you’re not likely to use one unless you’re on a ship.

Gyrocompasses are quite large and expensive, so they’re not practical for outdoor recreational use in the mountains.

However, there are other types of compasses. These include:

- Liquid Compass. This is the type most of us are familiar with and the type we’ll discuss here. A liquid compass has a magnetized needle that’s immersed in a fluid that allows the needle to spin freely toward magnetic north.

- Card Compass. Card compasses have a fixed needle and a spinning card that’s immersed in fluid. The card has directional markings and will spin to give you the direction relative to magnetic north. This kind of compass is most commonly used on ships and boats because the card is easier to read than a small needle while your vessel moves around in the water.

- Solid State Compasses. A solid state compass is what’s found inside a mobile phone or other electronic devices. They have 2-3 built-in magnetic field sensors that give the processor information about the orientation of the phone so you can find your way.

Why Should I Learn To Use A Compass?

A compass might seem like an archaic piece of gear when compared to a piece of technology like a GPS. While it’s true that a GPS can be a fantastic navigational tool, they are not the end-all-be-all in the real world.

Of course, knowing how to use a GPS efficiently is also a useful skill. But, a GPS can break, malfunction, or simply be out of battery. If any of these things happen and you need to navigate in a remote location, you better hope that you’re competent with a compass.

A compass, on the other hand, will work in nearly any situation. Unless your compass is physically broken, affected by local metals (called deviation), or not designed for the hemisphere that you’re in (more on that later), you can use it to navigate.

Since deviation and hemisphere-related compass issues are not common if you’re bugging out or camping in the backcountry, the only likely reason that your compass wouldn’t work is if it was snapped in half.

But, then again, I’ve never seen a quality compass break from normal use. You’d have to run one over with a car or smash it with a rock if you wanted it to break.

Alternatively, we can probably all think of a time where technology has failed us. Whether it is a dead battery or a wet phone, the fact of the matter is that you don’t want to solely rely on technology to get you out of a bind.

That’s why you should learn how to use a compass to supplement your GPS skills.

How Does A Compass Work?

Since the vast majority of us will only ever use a liquid magnetic compass for navigation, we’ll focus on this kind of compass for the rest of the article. Thankfully, the way that a liquid magnetic compass works is quite simple.

Basically, the spinning needle in a compass is directed by the Earth’s natural magnetic field will point toward what’s known as magnetic north.

Magnetic north is different from geographical or “true” north (where the north pole is) because the Earth’s magnetic field is constantly moving.

In fact, magnetic north is slowly drifting around the Canadian Arctic. Magnetic north is about 310 mi (500 km) from true north, as of 2015.

I’ll talk more about how you can adjust your compass readings to tell you where you are in relation to true north in a bit.

But, the important thing is that you understand that a magnetic compass that’s functioning properly will point to magnetic north.

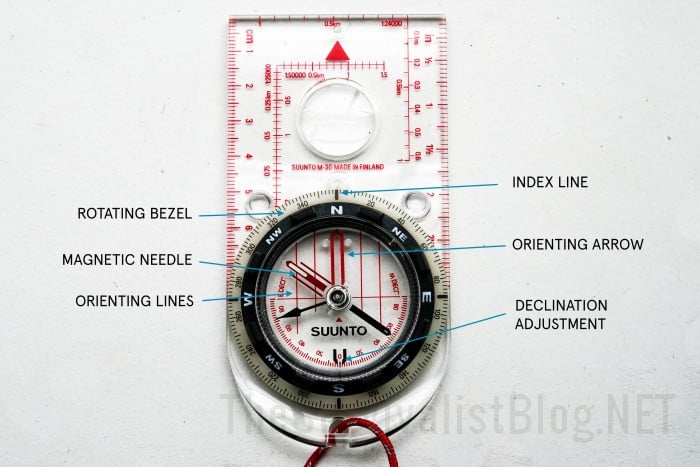

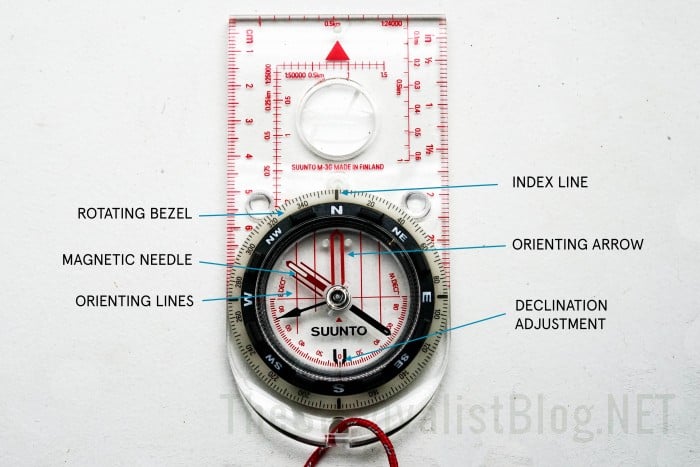

The Parts of a Compass

Before I dive into the process of using a compass, it’s important that you understand the different parts of the compass. Since I’ll refer to these parts in my directions on how to use a compass, it’s good to commit these names to memory.

Baseplate

The baseplate on a compass is its plastic foundation. A compass’ baseplate will almost always be clear so you can place it on top of a map but still see the map detail below.

Compass baseplates will also have at least one straight edge so you can draw bearings and courses on a map.

On the baseplate, you also have the following features:

- Direction Of Travel Arrow. The direction of travel arrow is the arrow at the top of the baseplate. Once you adjust your compass for the bearing you need and orient it toward north (more on that later), this direction of travel arrow is the one you follow.

- Rulers. On the side of a compass, you’ll usually have a few rulers. These can be useful for measuring distances on a map.

- Index Line. The index line is a small line located right above the rotating bezel. The index line is the line you use to read your bearing.

Rotating Bezel

The rotating bezel is the spinning foundation for the needle housing. The fact that this rotates is essential for navigation as it allows you to get precise measurements for bearings other than magnetic north.

The bezel is also called an azimuth ring and has 360-degree circle markings.

Needle Housing

The needle housing, as the name suggests, is the part of the compass that holds the needle. This is filled with fluid so the needle can spin freely. Inside the needle housing you have the following:

- Magnetic Needle. Without the magnetic needle, a compass is useless. The needle spins inside the housing and the red part points toward magnetic north.

- Orienting Arrow. The orienting arrow is the hollow red arrow inside the needle housing. Aligning the red end of the magnetic needle with the inside of the orienting arrow is the first step to shooting a bearing.

- Orienting Lines. Inside the needle housing, you have some orienting lines. These are used to align your compass with the grid lines on a map.

- Declination Adjustment. A quality compass will also come with declination adjustment lines. You can pre-set these to match the declination in your area for easy calculations (more on that later).

How to Read a Simple Compass

The simplest thing you can do with a compass is to figure out which way is north. To read a compass and determine which way is north, you’ll do the following:

- Hold The Compass Steady. You should always hold a compass so that the baseplate is parallel with the ground. Hold the compass with both hands.

- Line Up The Red Arrows. To determine north, you want to ensure the orienting arrow and the direction of travel are pointing in the same direction.

- Turn Until To Face North. Now, you’ll turn your whole body until the red end of the magnetic needle sits inside the red orienting arrow. A good mnemonic to remember this is to always put “red Fred in the shed.” Once you do this, you will be facing magnetic north. Congrats!

How to Use a Compass Step by Step

Now that you know how to orient yourself to magnetic north with a compass, we can start talking about how you can use a compass for navigation. Before we get too far ahead of ourselves, though, here are a few key things to remember:

- A Compass Points To Magnetic North. I’ll teach you how to adjust a compass to navigate according to true north in a bit. But, never forget that magnetic compasses point to magnetic north.

- Always Hold A Compass Level. If you tilt your compass too much, you can prevent the needle from spinning freely. Always hold your compass level and with two hands when shooting bearings (a.k.a. getting a direction).

- Don’t Follow The Magnetic Needle. A common mistake among new navigators is the tendency to follow the magnetic needle. Unless you’re trying to walk toward magnetic north, this is not a good thing to do. I’ll show you how to adjust your compass to give you the bearing you want, but remember that you should always follow the direction of travel arrow. It has that name for a reason!

- Always Turn Your Whole Body. When orienting your compass to magnetic north, you always need to turn your whole body. If you just move your hands, it will be difficult to read your compass and you might get an inaccurate bearing.

Okay, so, with those basic concepts in mind, let’s talk about how to use a compass. If you’re just navigating using a compass and no map, you have two possible things you can do: take a bearing and follow a bearing. Here’s what you need to do:

Taking a Bearing

When you take a bearing, you determine the position of an object, like a mountain, in relation to where you are standing.

This is useful if you are standing in an open area, like a field, and can see your destination but know that as you walk, you will not have clear sightlines the whole way.

Additionally, you can take a bearing of three obvious and known points (like mountains) and plot them on a map to determine your location.

This is called triangulating a position, and is a more advanced skill we won’t cover here.

To take a bearing, you’ll do the following:

- Hold The Compass Steady. Hold your compass steady and level with both hands.

- Turn To Face The Object. Turn your whole body so that you face the object of interest/landmark (usually a mountain or other obvious feature). The direction of travel arrow should face the object of interest.

- Rotate The Bezel. While holding the compass steady, rotate the bezel until the red end of the magnetic needle is sitting inside the orienting arrow. This is called putting “red Fred in the shed.”

- Read The Bearing. When the needle is in the orienting arrow, look at the index line and read the number right below it. That’s the bearing from you to the landmark.

Following a Bearing

Once you take a bearing, you can now follow it to reach your destination. In a perfect world, you would be able to simply walk with the compass in your hand and follow that bearing until you reach the landmark.

But, if you’ve ever tried to walk with a compass in your hand over tricky terrain, you’ll know that it’s incredibly difficult to stay on course over a long distance. So, you’ll want to do the following:

- Hold The Compass Steady. Hold your compass steady and level with both hands.

- Set Your Bearing. Ensure that your bezel is adjusted so your bearing is aligned with the index line. If it is not, you’ll walk in the wrong direction.

- Turn Toward Your Bearing. Turn your whole body so that the red end of the magnetic needle is sitting in the orienting arrow.

- Find An Object That’s directly In Front Of You. Since it’s hard to follow a bearing over a long distance, locate an intermediary object that’s along your path. This will be your first waypoint to ensure you stay on track.

- Start Walking. Once you put “red Fred in the shed, walk straight ahead” (it rhymes!). You will walk in the direction of the aptly named direction of travel arrow – not the magnetic needle. Keep walking until you reach your first waypoint. Then, repeat steps 1-4 to find additional waypoints until you reach your destination.

How to Use a Map and Compass

If you’re looking at a map and want to plot a course to follow between your location and another point, you’ll want to do the following:

Orient Your Map

If you don’t orient your map when you’re looking at it, it can be difficult to know which way you’re headed.

You actually need to orient your map to plot a course, but knowing which way your objective is before you start plotting bearings is a good way to double-check your math before you start walking in the complete opposite direction.

This is also helpful to do so you can get a good understanding of the terrain around you.

Here’s what you need to do:

- Place The Map On A Flat Surface. Your map should be placed on the ground or on a rock. Consider weighing it down with rocks to stop it from flying away.

- Use Your Compass. Place your compass on your map. Ensure the direction of travel line and the index line are aligned and pointing upward at the top of the map.

- Line Up Your Compass. Place one edge of your compass baseplate along the side of the map. Ensure the compass edge lines up with one of the vertical lines on the map.

- Rotate the Map And Compass. While holding the map and compass as steady as possible, turn them until the red needle is in the orienting arrow. Keep in mind that this will point your map toward magnetic north. If you’re in an area with a large declination (over 5º or so), you’ll definitely want to adjust your compass accordingly to ensure you’re orienting your map properly.

Plot a Bearing

If you know where you are on the map and you want to determine a compass bearing to follow to get to your destination, you’ll do the following:

- Place Your Compass On The Map. You’ll place your compass on the map so that the edge of the baseplate makes a straight line between your location and your destination. Ensure that the direction of travel arrow is pointing toward your destination. If not, your bearing will be 180º in the wrong direction!

- Rotate The Bezel. Rotate the bezel of the compass until the orienting lines inside the needle housing line up with the lines on the map.

- Read Your Bearing. When the bezel is lined up properly, look at the index line. The number under it is the true-north bearing for your destination.

- Adjust For Declination/Variation. Now, you need to adjust your true north map bearing so that you can use it with your compass, which requires a bearing that works for magnetic north. This is a potentially tricky topic, so we’ll cover it in detail next.

Adjusting a Compass for Declination/Variation

A magnetic compass points to magnetic north and not true north, while all maps are created according to true north.

This means that whenever we use a map and compass together, we need to make our compass and map speak the “same language” in order to navigate.

When using a map and compass together, we must adjust our compass for declination (a.k.a. variation if you’re from outside North America). Doing so makes the values that we read on our compass relative to true north.

The problem is that declination varies from location to location. While some places, like the United Kingdom, have very little declination (about 1º), others, like the Brooks Range of Alaska, have huge 40º declinations.

If you don’t adjust for declination in a place like northern Alaska, you will end up walking 40º in the wrong direction. That’s more or less the equivalent of walking east when you’re meant to be walking due south. This would be very bad, especially in a survival situation.

Thankfully, any map worth using for navigation will have a small declination guide that will tell you what the declination value is in that area. Keep in mind that declination changes from year to year, so read the map’s key to see if you need to increase or decrease the value.

A declination will be read as a number of degrees (for example, 6º) and will be either “east” or “west.” If you’re in the continental United States, it helps to think of the east/west divide as the Mississippi River.

So, if the Mississippi River is to the east of you, you will have an east declination. Conversely, if the Mississippi is to the west of you, you will have a west declination.

Once you know your declination value and direction, you can adjust your compass bearings accordingly. The acronym CADET is useful here. CADET stands for:

- Compass

- ADd

- East

- True

This might seem a bit confusing, so let’s break it down. Basically, if you’re going from your magnetic compass bearing and plotting it to a “true north” map bearing, you want to add the degree value for an east bearing.

If you’re going from a magnetic compass bearing and plotting it to a “true north” map bearing, you want to subtract the degree value for a west bearing.

Conversely, if you’re going from a “true north” map bearing to a magnetic compass bearing, you subtract the degree value for an east bearing. If you go from a “true north” map bearing to a magnetic compass bearing, you add the degree value for a west bearing.

If this is confusing, writing it down like this on your map is quite helpful for reference:

Once you’ve done this, you’ve successfully adjusted your compass for declination and can navigate as you normally would.

Using a Compass FAQ

Here are my answers to some of your most common questions about compasses…

Are compasses different in Tthe northern and southern hemisphere?

If you live in the northern hemisphere and buy a compass, it will almost certainly be a “northern hemisphere” compass. Conversely, if you live in the southern hemisphere and buy a compass, it will almost certainly be a “southern hemisphere” model.

Since compasses point towards magnetic north (never magnetic south!), the fact that we have southern and northern hemisphere-specific compasses can seem a bit confusing. The reason for this is that the Earth’s magnetic field isn’t perfectly straight.

As you get closer to the magnetic pole, the invisible lines of the magnetic field dip downward. In fact, if you were standing on the magnetic north pole, the invisible lines of the magnetic field are completely vertical and perpendicular to the ground.

To be precise, a magnetic compass needs to account for the variation in the position of the magnetic field. So, compass manufacturers add weights to the back end of the needle to help balance them out.

The vast majority of the compasses you buy will be weighted only to work in either the northern or the southern hemisphere. This is the cheaper option, which is why most people end up with a single-hemisphere compass.

You can buy a “global” compass that’s weighted for use in either hemisphere.

But, while you can get a Suunto A-10 compass for the northern hemisphere for a fair price, the Suunto M-3 G compass for global is definitely pricier.

So, unless you actually need a global compass, a single hemisphere option is probably more than sufficient.

What can affect the accuracy of a compass?

The main thing that can affect the accuracy of a compass is what’s known as “magnetic deviation.” Magnetic deviation happens when a compass is near an object that creates a local magnetic effect, like metal.

This is particularly problematic on boats and ships (as well as aircraft) that contain a lot of metal. In these instances, a compass will not always point toward magnetic north because of the effects of nearby metal.

To solve this issue, ships and planes will often have a “deviation card”, which shows you the inaccuracies of your compass at many different bearings.

Then, all you need to do is correct your reading using the information to get your new, more accurate bearing. Thankfully, this is not something that we generally have to deal with when we’re navigating in the backcountry.

Keep in mind, though, that “deviation” is different from “declination,” which is also called “variation” in some countries.

While deviation refers to the effect of metal and local magnetism on a compass, declination and variation have to do with the fact the magnetic north pole and true north pole not being in the same location.

Does a compass work at the North Pole? What about the South Pole?

If you were standing on the geographic north pole, your compass would not spin around in confusion. Why? Well, the geographic north pole is not the location of the magnetic north pole.

Compasses point to the direction of magnetic north, and not “true” north. So, at the true north, your compass would simply point toward magnetic north, which is slowly drifting around the Canadian Arctic at the moment.

At magnetic north, your compass wouldn’t move, because the place it points to is right where you’re standing.

At the geographic and magnetic south poles (which are 1,78 mi / 2,860 km apart), your compass would simply point toward magnetic north.

The magnet in your compass is not designed to point to the magnetic south pole, so it will continue pointing toward magnetic north, regardless of the fact that you’re standing on the bottom of the Earth.

Can a compass freeze?

Even though a compass’s needle housing is full of fluid, it’s not likely to freeze on your next camping trip, no matter how cold it gets. The fluid inside the needle housing is almost always a mixture of alcohol and distilled water.

While water freezes at 32º F (0º C), rubbing alcohol (isopropyl) doesn’t freeze until a chilly -117º F (-82º C). The lowest temperature ever recorded on Earth was a balmy -135º F (-94º C) at Russia’s Vostok Station in Antarctica.

Additionally, the coldest temperature ever recorded in a town was -90º F (-67.7º C) in Oymyakon, Russia in 1993. So, unless you’re planning on overwintering on the White Continent, your compass probably won’t freeze.

Are bubbles bad for a compass?

A compass can develop bubbles inside its needle housing due to changes in elevation, pressure, and temperature. The good news is that most bubbles will disappear when the compass returns to a normal elevation and temperature.

Plus, small bubbles don’t necessarily affect the accuracy of your compass. If you have one large bubble, though, that’s affecting the movement of the needle, that could be problematic.

If you want to try to remove bubbles from your compass, try placing it in a warm spot – like in the sun – and the heat will likely return everything back to normal.

Using a Compass: An Essential Skill

The ability to use a compass is critical in a true wilderness survival situation. Navigational skills are one of the most important things to develop, especially if you spend a lot of time outdoors.

While the goal is to always “stay found,” if you ever feel like you’re getting lost or that you don’t know which way to head, compass skills could make a huge difference when SHTF.